There is a large community of hard-working people who are on the brink of financial fragility in Ellis County, a recent national report found.

It is a population of people that could be our neighbors, little league coaches, teachers or even church volunteers. “These are people you know,” explained Kasey Cheshier, Executive Director of United Way of West Ellis County. He also noted these residents live paycheck-to-paycheck and are one crisis away from falling below the poverty line.

The Unity Ways of Texas has released data this week that showed 4,025,176 households could not afford basic needs in Texas in 2016, equating to 42 percent of the homes across the state.

The research also found 27 percent of Ellis County households fall under the ALICE definition, and 10 percent live in poverty as defined by the federal poverty guidelines.

The data was pulled from the ALICE report, which was released by the United Way of Texas on Tuesday. ALICE — which stands for asset limited, income constrained, employed — focuses on a population of residents who work low-paying jobs that have little or no savings and are one emergency away from falling into poverty.

“These are people you know. It’s family, your neighbors, people you know at your church. They might not be able to be identified,” Cheshier said.

Information gathered for the report came from a variety of resources such as the Housing and Urban Development, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Internal Revenue Service, Tax Foundation, the U.S. Census and the American Community Survey.

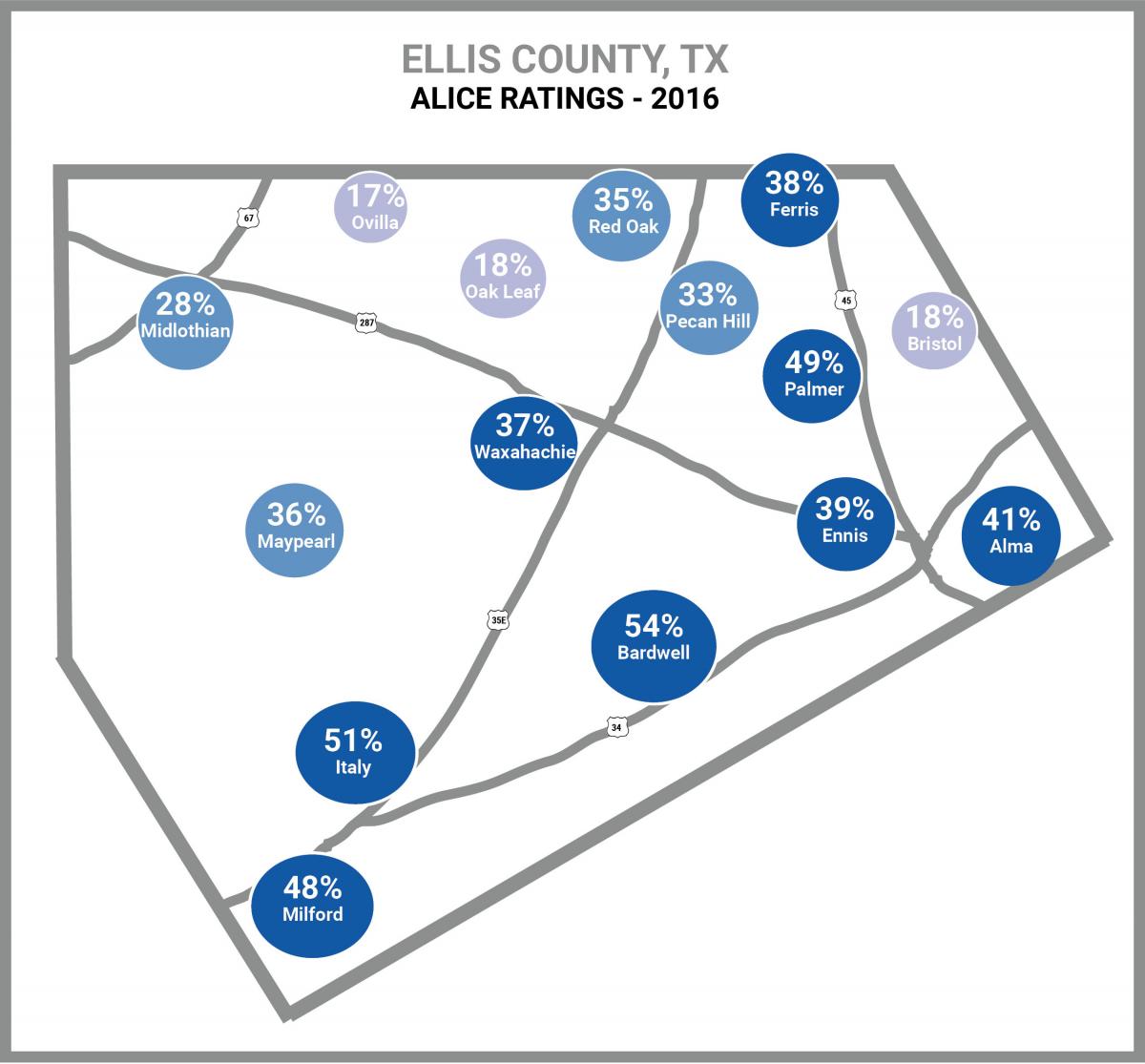

UWWEC provided additional data that documented Bardwell with the highest percent of ALICE with 54 percent Cities that trailed include Italy (51 percent), Palmer (49 percent), Milford (48 percent), Alma (41 percent), Ennis (39 percent), Ferris (38 percent), Waxahachie (37 percent), Maypearl (36), Red Oak (35 percent), Pecan Hill (34 percent), Midlothian (28 percent), Bristol (18 percent), Oak Leaf (18 percent) and Ovilla (17 percent). — COURTESY UNITED WAY OF WEST ELLIS COUNTY

ALICE by sub-county

This map is broken down by sub counties, which include Midlothian, Waxahachie, Ferris, Maypearl, Ennis and Italy. Data gathered from this interactive map discloses the number of households, and percentages for poverty, ALICE and above ALICE threshold. Data is compiled to represent 2016.

MIDLOTHIAN

- Households — 7,937

- Poverty — 8%

- ALICE — 24%

- Above ALICE — 68%

FERRIS

- Households — 4,509

- Poverty — 11%

- ALICE — 37%

- Above ALICE — 52%

ENNIS

- Households — 9,064

- Poverty — 20%

- ALICE — 38%

- Above ALICE — 42%

WAXAHACHIE

- Households — 28,598

- Poverty — 8%

- ALICE — 30%

- Above ALICE — 62%

ITALY

- Households — 1,553

- Poverty — 14%

- ALICE — 46%

- Above ALICE — 40%

*Information provided by the United Ways of Texas

Cheshier, who has been a Midlothian resident for nine years, admitted, “When I read the report it blew me away.”

The percent of ALICE residents in Ellis County do fluctuate by the city.

UWWEC provided additional data that shows Bardwell to have the highest percent of ALICE household (54 percent). Cities that followed on the report included Italy (51 percent), Palmer (49 percent), Milford (48 percent), Alma (41 percent), Ennis (39 percent), Ferris (38 percent), Waxahachie (37 percent), Maypearl (36 percent), Red Oak (35 percent), Pecan Hill (34 percent), Midlothian (28 percent), Bristol (18 percent), Oak Leaf (18 percent) and Ovilla (17 percent).

Roxanne Jones, senior vice president of United Ways of Texas, has been with the nonprofit for the past 17 years and has a background in business. She further detailed the ALICE data for Ellis County.

“Those rural areas tend to have ALICE because of the [few] opportunities to receive higher paying jobs,” Jones explained. “There’s not a lot of corporate business that falls into rural areas.”

Data compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics detailed the number of jobs offered by the size of the company and the average salaries in Ellis County. This data showed smaller businesses provide more jobs but also a lower wage when compared to larger firms that employ 500 people or more.

The ALICE report also provided a table that details the bare minimum an individual and a household of two adults, one infant, and one preschooler, would have to earn to live in Ellis County. This information is referenced as the “household survival budget.”

The breakdown includes the cost of housing, child care, food, transportation, health care, technology, miscellaneous and taxes.

For a person in Ellis County to survive, a single adult would need to make an hourly wage of $11.23. For a family, the minimum hourly wage would be $33.47.

As for the rest of the state, the averages show a single adult needs a $9.71 hourly wage, while a family needs $26.48 to survive.

From 2010-16, the total number of households in Ellis County has grown by 5,988. Data provided by the American Community Survey showed households by income were stagnant over that time.

The poverty rate remained around 10 percent and the ALICE threshold has been between 29 and 26 percent, while those above the ALICE threshold stay in between 62 and 64 percent in Ellis County.

The United Ways of Texas reported the population in Ellis County grew at around 22 percent from 2007-16. Jones said despite growth, it is only natural for household incomes in Ellis County to not fluctuate if large corporations have not gone out of business or been established.

When it comes to families with children, the 1,046 single male-headed households accounted for had the worst figures. In this category, 49 percent were considered ALICE, 30 percent were in poverty, and 21 percent were above the ALICE threshold.

A total of 3,956 single female-headed households were documented with 37 percent considered ALICE, 47 percent in poverty and 16 percent above the ALICE threshold.

Married households —14,448 homes — had the most positive figures with just 24 percent ALICE, three percent in poverty and 73 percent above the ALICE threshold.

“I don’t think anything jumps out to me for Ellis County,” Jones noted. “I think just, overall, the idea that the gap between where the federal poverty level is and the ALICE budget threshold is such a large gap.”

She continued, “I think this is when we have discussions around who is ALICE in our community and what are the kind of conversations we can have in our community to begin to address ALICE and what that looks like for us.”

Stephanie Bowman, the UWWEC program director in Midlothian, said, “There is more [need] here than what people realize; we just don’t see it.”

Cheshier expressed hope that the ALICE report would make this information relevant to communities and educate people on a group of people who are in need but may not look like it from the outside.

“There’s not one magic bullet that will fix this problem; it’s a systematic issue,” Cheshier said. “When we look at this data from a United Way standpoint, it’s ‘how do we convene all these separate entities together?’”

He advocated for government entities, financial backers, churches, school districts and nonprofits begin a dialog on how a group effort could identify solutions to benefit the ALICE population in Ellis County. Cheshier expressed the ALICE report is the reason to initiate this conversation.

MEETING NEEDS IN ELLIS COUNTY

The question whether the needs of ALICE people were met came up in conversations with Cheshier and Jones.

Two nonprofits, Manna House and Waxahachie CARE, shared their 2018 data with the Daily Light to help answer that question.

Manna House is a community outreach organization that serves the needs of Midlothian residents and those in Midlothian ISD. The vision of the nonprofit is to provide a helping hand when a crisis comes unexpectedly and to empower clients to stability to build a stronger and healthier community.

When Manna House Executive Director Sissy Franklin was informed about the ALICE report, she strongly expressed those hard-working individuals and families have been served.

When asked about the demographic that typically uses the aid from Manna House, Franklin expressed these people are “our neighbors, our friends, strangers — everybody has that breaking point. Stuff happens, and it can happen to anybody.”

She too experienced a crisis that had her walking in the front doors of Manna House after she became ill with a noncancerous brain tumor in 1999. She explained that she and her husband both worked and lived comfortably. She even volunteered at Manna house for 10 years before becoming an employee.

“One day on my way home from work I was done,” Franklin recalled. “I was in the middle of a humongous seizure. I went into a grocery store I’ve never been to and put items in my basket that I’ve never purchased before. I got up to the register, and my speech was slurred. I thought I was having a stroke. I passed out at the register.”

A police officer at the store called her emergency contact, and Franklin was taken to the hospital. Two weeks later an egg-sized tumor was removed from her brain. Franklin had to learn how to speak again.

“So, it was like the rug was pulled out from under us,” Franklin reconciled.

She explained some people have situations that are so deep that it takes a couple of visits before the individual is back on their feet. Meanwhile, with other clients, Franklin ensures they are provided the tools and classes to maintain a balanced life. She said some classes are mandatory for an individual to acquire help.

“It’s important for me that my entire staff knows what it feels like to walk in the door and at one time or another it’s been years or decades, but we have all been there,” Franklin said. “Every single one of my staff has had to ask for help at no fault of their own.”

According to data provided by Manna House, 14,354 individuals were helped in 2018. A total of 348 families sought financial assistance, which equated to $36,830.52. Nearly a million pounds of food was provided through the food pantry, and approximately 4,500 children were fed in the summer feeding program.

Franklin said her team tries to address each crisis that comes in or help lead an individual to the appropriate agency for help.

“We don’t try to get them through life, we try to get them through the crisis,” Franklin emphasized.

Another nonprofit, Waxahachie CARE, also provided its figures of aid to Waxahachie and south Ellis County. The organization operates a food pantry and offers financial assistance for clients, which Waxahachie CARE staff and volunteers reference as “neighbors.”

Waxahachie CARE assisted 6,613 individuals in 2018. That figure converts to 4,234 families. Out of those helped, 372 were new families.

The nonprofit manages the intake process for the utility companies such as, TXU Energy, Reliant and Atmos Energy, that help pay bills for Waxahachie CARE neighbors. Data showed 481 people — some are duplicated as they have multiple bills to pay — benefited from utility bill payments.

The City of Waxahachie also gives its customers an option to send extra money with their paid water bill to go into a water fund to help others pay their bill. Waxahachie CARE manages this intake process. In this account, the nonprofit served 28 people with $2,139.

Waxahachie CARE Executive Director Kim Holman, noted, “If their customers do not give extra, this service is reduced to just what CARE can help with.”

Waxahachie CARE helped 139 people with water and propane expenses in the amount of $11,584.34. “This money is set aside to do our part in giving back to help our neighbors,” Holman stressed.

As of food, the nonprofit is partnered with the North Texas Food Bank, which has established guidelines. Those guidelines require a family of one to make $22,459 annually or $1,872 a month to qualify. As the number in each family increases these numbers change.

Other qualifications include if a member of the family is on Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Supplemental Security Income, National School Lunch Program or Medicaid, they automatically quality regardless of income.

The North Texas Food Bank requires recertification annually.

“We went through that recertification in January and are continuing through February,” Holman said. “If our neighbor comes in the middle of the year and qualify, their year begins but each new year starts over with new paperwork.”

Additionally, if a family member has had a catastrophe, major illness or significant upset within the family that has caused a financial burden, Waxahachie CARE can help for six months with food.

Holman noted that Waxahachie CARE has qualifications that mirror those of the North Texas Food Bank and proof of income and residency is required. Each neighbor can shop once a month.

“If a neighbor is homeless we will help with food also,” Holman said. “Each situation is different, so sometimes we allow shopping more than once a month, but the amount of food is smaller to accommodate them.”

Cheshier, Franklin and Holman all agreed the need in Ellis County is food and utilities.

Featured in the Waxahachie Daily Light - Feb 2019